“I was quite a character. I was a little terror,” says legendary graffiti artist, Lady Pink down the telephone from New York. In fact, I have already been assured of this by Wild Style director, Charlie Ahearn who recently told us that she was one of the most determined (and impressive) characters of the 1970s/80s NYC graffiti community.

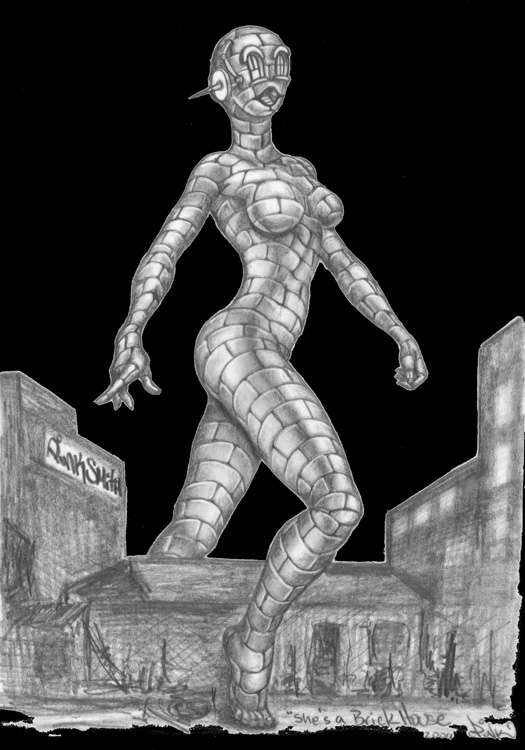

For the heavily male-dominated writing culture, the appearance on the scene of a petite and pretty teenage Lady Pink in her high heels, dresses, make-up, and with a bag of aerosol cans, must have caused quite a stir. Initially, she had to work to prove herself among these guys who “tested me, they put me through the ringer. I had to prove that I was sturdy and brave and reckless and foolish, just like them.”

For the heavily male-dominated writing culture, the appearance on the scene of a petite and pretty teenage Lady Pink in her high heels, dresses, make-up, and with a bag of aerosol cans, must have caused quite a stir. Initially, she had to work to prove herself among these guys who “tested me, they put me through the ringer. I had to prove that I was sturdy and brave and reckless and foolish, just like them.”

She first began her writing career following the loss of a boyfriend who had been sent to live in Puerto Rico after he had been arrested. She exorcised her grief by tagging her boyfriend’s name across the city, but “it didn’t make me stand out. The idea in graffiti is to get fame. The more you get noticed, and if it isn’t exactly by skills, it’s by doing some crazy, outrageous thing or just being like the only girl out of 10,000 guys.” So she evolved her tag to Lady Pink—a product of her love of historical romances, England, the Victorian period and the aristocracy.

Of the lack of female writers working in graffiti back then, she says: “Real illegal graffiti is a very hard, scary, manual, labour-intensive, stressful kind of a job…You also have to have a criminal streak… And that field is not nearly as full of women as it is of guys. Artistic talent is optional. You gotta have the guts. It’s hard, disgusting work. All for what? Very little glory, no profit? The guys do it to prove their machismo. They do it for themselves, for others, for the chicks. They get fame, they’re outlaws—it’s so appealing. There are not nearly as many benefits for females unless they need that kind of excitement for kicks.”

It was this ‘excitement for kicks’ that attracted Pink to the outlaw art world, but she soon transcended to the galleries and at just sixteen-years-old, she was already mixing in the upper echelon of New York’s art scene. “I quickly forgot that first boyfriend and just fell in love with the adventure, the excitement, the thrill part of belonging to a great big culture in New York. At sixteen, I started exhibiting in galleries and running in the crowd of older, more respected graffiti writers like Dondi. With Keith Haring, Basquiat, Andy Warhol — in those kinds of circles,” she explains.

The subway art that brought her all this attention was, she says, executed as quickly and quietly as possible. “It can be labelled a military manoeuvre but then that would imply there is a leader and everyone listens. That is not true. It’s just a bunch of drunken kids stumbling into a train yard, trying to do the impossible with very little stolen supplies and maybe the oldest of the bunch is all of fifteen or sixteen. You’d go with someone that knows the place so that you can go in there quietly: climbing walls, down huge ladders, walking through these dark creepy tunnels, dodging live trains. People held their spots very tight ’cause if you passed it around, they’ll burn your spot. So that hole in the fence was your secret… Then, you put a few beers down a guy and he’ll cough up anything,” she laughs.

The ascension into the galleries and the sudden interest from filmmakers, provided a fast avenue to fame for artists like Lady Pink: “Give a high-school kid thousands and thousands of dollars, your name at the door at the best clubs, V.I.P treatment, drink and drugs and cute guys, oh yeah, it’s a hard choice. At the time there was a lot going on, everything exploding. Weird men wanted to make films and photo shoots and this and that. Everything was going on. It was a whirlwind of activity and I vaguely remember it, I was so young. I have written it all down though. I kept a journal. It’s so, so very personal, I’d have to wait till a few more people drop dead before I could ever publish that.”

The ascension into the galleries and the sudden interest from filmmakers, provided a fast avenue to fame for artists like Lady Pink: “Give a high-school kid thousands and thousands of dollars, your name at the door at the best clubs, V.I.P treatment, drink and drugs and cute guys, oh yeah, it’s a hard choice. At the time there was a lot going on, everything exploding. Weird men wanted to make films and photo shoots and this and that. Everything was going on. It was a whirlwind of activity and I vaguely remember it, I was so young. I have written it all down though. I kept a journal. It’s so, so very personal, I’d have to wait till a few more people drop dead before I could ever publish that.”

Her recollection of the movie Wild Style—in which she played a starring role—might give an indication of just how ‘personal’ such a book might be. She says: “I did have a real relationship with Lee [Quinones] and that’s how Charlie made up his movie. He just wrote stuff that he saw around him… He put the real love relationship between me and Lee, and called it the king and queen of graffiti. We had a very stormy relationship for about four years. They had to hold up filming because I was crying, he’s screaming, we’re not getting along. The lighting people, the sound people, they’re all waiting! It was awful! I convinced Lee to do that part. They actually auditioned like a couple of dozen people and then I finally talked him into doing it. He never wanted to do it and he never did publicity after. He had a lot of issues with it. I twisted his arm and made him do it, kicking and screaming.”

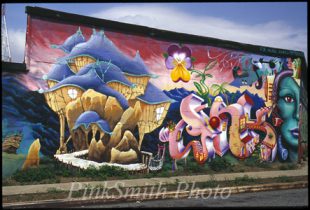

Despite her ongoing success—the high demand for her commissions, not to mention the mural company she now runs with her husband and fellow artist, Smith—to New York’s Vandal Squad, Lady Pink is still on their radar, even though she no longer works illegally. The lasting impact of her notoriety has been a double-edged sword. She explains: “I inspire all kinds of people, but because I inspire young people, I should be outlawed. They would like me to stop. The Vandal Squad have told me ‘stay in your little inside galleries where it is safe’.

“They even got into my house three years ago. They took all my stuff, all my photos, everything. It took me a year to get it all back—and not all of it even— and there were no charges filed. Legally, they can have an open investigation for a year. So the most they can do is just harass me, make me spend money on a high-priced lawyer, harass me some more and just torture me because I insist on coming out to do public walls…They even tried to get some little punks to paint over my walls. When they arrested some guy I never even knew existed, they said I [had] rat him out, so this kid was gonna’ go out on a vendetta and take out all our murals. I mean, they’ll try anything. The police are low. It is a crime, but when you take it above ground and you get paid for it, it’s still a crime in their eyes because now you’re profiting from this.”

“They even got into my house three years ago. They took all my stuff, all my photos, everything. It took me a year to get it all back—and not all of it even— and there were no charges filed. Legally, they can have an open investigation for a year. So the most they can do is just harass me, make me spend money on a high-priced lawyer, harass me some more and just torture me because I insist on coming out to do public walls…They even tried to get some little punks to paint over my walls. When they arrested some guy I never even knew existed, they said I [had] rat him out, so this kid was gonna’ go out on a vendetta and take out all our murals. I mean, they’ll try anything. The police are low. It is a crime, but when you take it above ground and you get paid for it, it’s still a crime in their eyes because now you’re profiting from this.”

Now that the lines between the street and the commercial art world are becoming increasingly narrow, what constitutes a graffiti artist in today’s culture? “As long as it’s vandalism, and you can be arrested and charged for vandalism, then it’s graffiti,” she asserts. “If you’re not willing to break the law, then you are just an artist. If it’s illegal, it is maintaining the spirit of rebellion. And this is the true meaning of graffiti.” This ‘spirit of rebellion’ so integral to the culture, exists, she believes, because artists have “always been a thermometer for our culture and the most outspoken kind of people. But as graffiti artists, as anonymous artists, we are kind of the last voice of freedom—like pirate radio stations—of free speech to express ourselves.”